The "Oopsie" of That Awful Amicus Brief

... and how it served the SBC's institutional ends

Last week brought news that, for many child sex abuse survivors, was hard to stomach. The Kentucky Supreme Court sided with the Southern Baptist Convention to shut down the ability of child sex abuse survivors to seek civil justice against abuse enabling institutions.

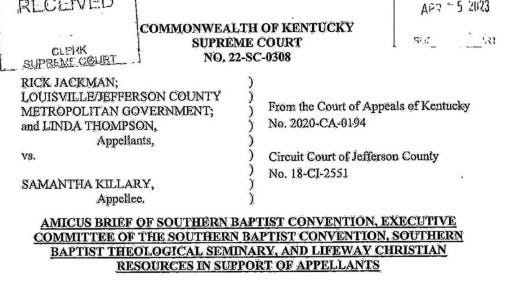

The SBC wasn’t even a party to the lawsuit—Jackman vs. Killary—but the SBC had deliberately inserted itself into the case by filing an amicus brief.

That filing was a duplicitous action that squarely contradicted the “we care” public posturing of SBC officials and instead put the full weight of the country’s largest Protestant faith group on the side AGAINST justice for survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

The duplicity paid off. No surprise in that. The SBC is a behemoth of power, and that’s exactly why it filed that brief—to bring to bear the influence of a massive constituency.

The court’s dissenting opinion succinctly summed up the scenario:

“Today’s decision again gives a windfall to the perpetrators and enablers of childhood sexual abuse, who once more reap the wholly unjust benefit of avoiding liability on the legal technicality of an expired statute of limitations.”

And that, of course, is exactly what the SBC wanted—what it argued for.

Again and again, we have seen that the SBC’s number one priority is protecting denominational dollars against liability risks. The Guidepost report documented that, and nothing has changed, as the amicus brief demonstrated.

But let’s backtrack a bit and look at exactly how that amicus brief got filed on behalf of the whole SBC. Who made that decision to put the whole of the SBC behind such an anti-survivor stance?

SBC president Bart Barber said that he did it. Barber “approved the SBC’s participation” in the brief.

But by Barber’s aw-shucks telling of how it came about, it was just a big “oopsie.”

When first asked about it, Barber said he scarcely remembered doing it because he was so very busy at the time. In his own words, he “did not give this decision to file this brief the level of consideration that it deserved.”

This was a matter of enormous consequence for child sex abuse survivors, but for Barber, his attitude toward it seems to have been almost cavalier—by his own admission—and that fact only rubs salt in the wound.

But hey… please don’t hold his “oopsie” against him, he suggests, because just the day before he had appointed the members of the Abuse Reform Implementation Task Force. So you see… he really really cares.

(I hope you’ll pardon my sarcasm, but in truth, I can’t manage this any other way. Barber seems to think we should take this sequence of events as proof of his good intentions. But to me, the fact that he approved the amicus brief the very day after appointing the task force looks like still more duplicity. The news of the task force appointments covered for and deflected from the reality of his behind-the-scenes maneuver of approving that amicus brief—a maneuver that stayed secret for months.)

Barber even goes so far as to suggest that maybe he didn’t really even have the power to approve the amicus brief on behalf of the SBC.

“Does it even lie within the power of the SBC President to make decisions about amici curiae unilaterally on behalf of the Convention?” he asks. “I think probably not.”

Again … “oopsie.”

Now you might think that, since Barber had the power to make an “oopsie” to approve the amicus brief, he could have also made an “oopsie” to rescind it. But of course, that never happened.

The SBC president exercises power when it’s convenient and pleads “no power” when it’s not convenient.

And Barber’s “oopsie” was incredibly convenient and self-serving for the institution of the Southern Baptist Convention.

The brief functioned to inform the Kentucky Supreme Court that the whole of the Southern Baptist Convention was taking a stand against the ability of child sex abuse survivors to seek justice in a court of law.

Barber wasn’t alone in this power play. The SBC Executive Committee, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and LifeWay Christian Resources all signed off on that amicus brief, too. It was a full-on SBC pile-on.

In the brief, all four of them described themselves as defendants in a separate Kentucky lawsuit and as “non-perpetrator third parties who were allegedly made aware of the abuse and violated common-law duties in responding to it.” Obviously, they were trying to protect themselves from liability in the separate lawsuit by influencing the development of Kentucky law in the Killary case.

Yet, when news of the brief hit the press, many Executive Committee members claimed to have been blind-sided by the brief. Some said they were “furious” and “livid” about it. “We had no working knowledge” of it, said one member.

“Executive Committee Officers” then issued a mealy-mouthed statement (with no name attached) saying that they had joined the brief “on the advice of legal counsel and only in response to their request.” Southern Seminary president Al Mohler parroted this, but without as much verbiage, saying “we refer all questions to legal counsel.”

So… rather than even having the decency to take responsibility, they seemed to be saying “blame it on the lawyers.” And of course, they reminded us that they’re really good guys because, after all, they have “empathy for survivors of sexual abuse.” (My eyes are literally rolling back in my head now.)

Meanwhile, LifeWay, who likely instigated the brief, gave no comment at all.

There’s no mistaking the bottom line in all this. It’s self-evident.

Even with so much public posturing, and even with Barber’s claim that his role was an “oopsie,” no one ever did a thing to make right the “oopsie,” or to retract the brief.

That failure wasn’t yet another “oopsie;” that was a choice.

They had months. They could have. They didn’t. None of them.

Why?

Because that brief did exactly what they wanted it to do. It served the money-protecting ends of the Southern Baptist Convention and its entities. The fact that it eviscerated the ends of justice for child sex abuse survivors was never their concern.

And the whole “oopsie” thing? I figure that was just a cover for public perception purposes.

No matter how much SBC officials say they care about clergy sex abuse survivors, that amicus brief showed what’s true: They don’t.

Yes, the fact that they did nothing, even after they found out the 'mistake' reveals the truth. This is a repeated pattern. A consistent choice. Their actions show what is true, not their words.